Welcome to August! This month, I have the pleasure of kicking off our topic: journeys and story structures in epic fantasy.

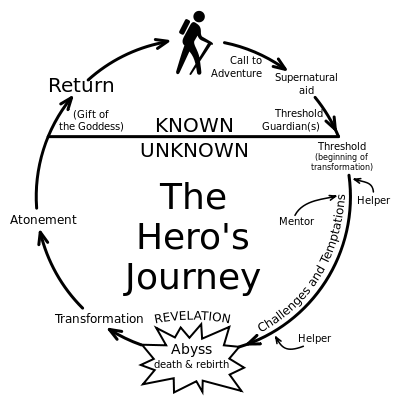

I’m sure you’re all familiar with Joseph Campbell’s the Hero’s Journey, also known as the Monomyth. Here’s a great article that explains it if you’re not:

http://www.thewritersjourney.com/hero’s_journey.htm

The Hero’s Journey defines many a fantasy book. In fact, many fantasy writers who first start out, steeped in Tolkien or other writers who followed closely the plot archetype as modeled in Lord of the Rings, will adhere quite closely to the Hero’s Journey. This month, our goal is to explore how writers can break free of these roots, which, most readers (and editors and publishers) will argue, have become cliched in epic fantasy fiction.

The Hero’s Journey defines many a fantasy book. In fact, many fantasy writers who first start out, steeped in Tolkien or other writers who followed closely the plot archetype as modeled in Lord of the Rings, will adhere quite closely to the Hero’s Journey. This month, our goal is to explore how writers can break free of these roots, which, most readers (and editors and publishers) will argue, have become cliched in epic fantasy fiction.

The first step away from this is to step outside the box and ask just what story structure is; this is the first step toward gaining greater insight to the tools at one’s disposal when writing any story. Epic fantasy is no exception, and in our modern age of fiction, there’s all the more reason to explore whole universes of story in this sub-genre that are left uncharted due to adherence to derivative form, rather that bottom-up construction.

What is story structure? Simply put, story structure is plot, and over time, plot has come in many forms. Some work, while others don’t. We all know what it’s like to read a book that has no effect, or watch a movie that makes us want to walk out. Over time, through studying the stories that “worked” (keyword: moved their audiences), story analysts have been able to determine some fundamental plot archetypes which crop up in these any stories, and seasoned writers have learned the value of sticking within these archetypes, and the inherent risk associated with deviating from them.

The attempt to define what makes effective plot goes back to Aristotle. Plot (called mythos) was considered more important even than character. Aristotle did not have much to say about structure (just that plot has a beginning, middle, and end), but he did have a lot to say about what that structure must do: it must arouse the emotion of the audience.

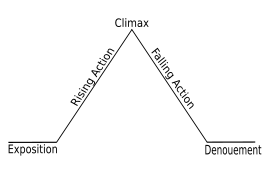

Aristotle explored the mechanics of tragedy (unfortunately, his work on comedy hasn’t survived), and out of this came, in 1863, Gustav Freytag’s pyramid.

Freytag took Aristotle’s simple 3-part plot one step further, creating the familiar 5 components many screenplay writers and outliners are familiar with — Exposition, Rising Action, Climax, Falling Action, Denouement.

But Freytag’s structure doesn’t say a lot about what substantive components an effective story should have. The Monomyth is one such outline of components, but what are the others?

George Polti’s, a French writer from the 19th century, laid out his 36 Dramatic Situations (published in 1916 in English and commonly used by playwrights and storytellers from that time forward). Here is the complete list:

- Supplication (in which the Supplicant must beg something from Power in authority)

- Deliverance

- Crime Pursued by Vengeance

- Vengeance taken for kindred upon kindred

- Pursuit

- Disaster

- Falling Prey to Cruelty of Misfortune

- Revolt

- Daring Enterprise

- Abduction

- The Enigma (temptation or a riddle)

- Obtaining

- Enmity of Kinsmen

- Rivalry of Kinsmen

- Murderous Adultery

- Madness

- Fatal Imprudence

- Involuntary Crimes of Love (example: discovery that one has married one’s mother, sister, etc.)

- Slaying of a Kinsman Unrecognized

- Self-Sacrificing for an Ideal

- Self-Sacrifice for Kindred

- All Sacrificed for Passion

- Necessity of Sacrificing Loved Ones

- Rivalry of Superior and Inferior

- Adultery

- Crimes of Love

- Discovery of the Dishonor of a Loved One

- Obstacles to Love

- An Enemy Loved

- Ambition

- Conflict with a God

- Mistaken Jealousy

- Erroneous Judgement

- Remorse

- Recovery of a Lost One

- Loss of Loved Ones

Taking a more global approach, William Foster Harris, in his 1959 book The Basic Patterns of Plot, argued that there were only only three kinds of plot archetypes: Type A, the happy ending; Type B, the unhappy ending; Type C, the literary plot. Ronald B. Tobias extended this in his 1993 book 20 Master Plots:

- Quest

- Adventure

- Pursuit

- Rescue

- Escape

- Revenge

- The Riddle

- Rivalry

- Underdog

- Temptation

- Metamorphosis

- Transformation

- Maturation

- Love

- Forbidden Love

- Sacrifice

- Discovery

- Wretched Excess

- Ascension

- Descension

Some storytellers like to think of plot archetype in a broader sense, focusing on the seven fundamental themes:

- woman vs. nature

- woman vs. woman

- woman vs. the environment

- woman vs. machines/technology

- woman vs. the supernatural

- woman vs. self

- woman vs. god/religion

Yes, I am a feminist (I’m also in the middle of reading Ann Leckie’s Ancillary Justice, where all people are referred to by the feminine pronoun by one of the main viewpoint characters, even if they are “of the male form”).

The plot archetypes I find the most useful, and which are most commonly cited by creative writing instructors today, come from the 2004 work of Christopher Booker (Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories), wherein, via Jungian analysis, he distills the works of his predecessors into an elegant collection of seven:

Overcoming the Monster: The protagonist sets out to defeat an opposing force (usually evil) which threatens her and/or her homeland. Examples:

- Beowulf

- Dracula

- War of the Worlds

- the James Bond franchise

- Star Wars: A New Hope

- Halloween

- The Hunger Games

- Harry Potter

Rags to Riches: The protagonist starts out poor and acquires things such as power, wealth, and a mate, before losing it all and gaining it back upon growing as a person. Examples:

- Cinderella

- Great Expectations

- The Prince and the Pauper

The Quest: The protagonist and some companions set out to acquire an important object or to get to a location, facing many obstacles and temptations along the way. Examples:

- The Pilgrim’s Progress

- Watership Down

- The Lord of the Rings

- Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows

- Indiana Jones

- The Voyage of the Dawn Treader

Voyage and Return: The protagonist goes to a strange land and, after overcoming the threats it poses to him or her, returns with nothing but experience. Examples:

- Alice in Wonderland

- The Time Machine

- The Hobbit

- Gone with the Wind

- Chronicles of Narnia

- Finding Nemo

- Gulliver’s Travels

- The Wizard of Oz

Comedy: Broadly speaking, this can be a dramatic work in which the central motif is the triumph over adverse circumstance, resulting in a successful or happy conclusion. Booker makes sure to stress that comedy is more than humor. It refers to a pattern where the conflict becomes more and more confusing, but is at last made plain in a single clarifying event. Most romances fall into this category. Examples:

- A Midsummer Night’s Dream

- Much Ado About Nothing

- Twelfth Night

- Bridget Jones Diary

- Four Weddings and a Funeral

- Mr. Bean

Tragedy: The protagonist is a hero with one major character flaw or great mistake which is ultimately her undoing. Their unfortunate end evokes pity at their folly and the fall of a fundamentally “good” character. Examples:

- Macbeth

- The Picture of Dorian Gray

- Bonnie and Clyde

- Romeo and Juliet

- Julius Caesar

- Breaking Bad

- Hamlet

Rebirth: During the course of the story, an important event forces the main character to change their ways, often making them a better person. Examples:

- Beauty and the Beast

- A Christmas Carol

- Despicable Me

- How the Grinch Stole Christmas

- Gravity

Another approach that I like is Kurt Vonnegut’s plot curves. Here is a fun video from the man himself explaining the approach:

I mention this because just last year, Matthew Jockers, a University of Nebraska English professor, exploring his field of specialty (digital humanities) ran a computer analysis on the database of known stories to confirm that, indeed, there are six (and sometimes seven) fundamental story archetypes, conforming to the fundamental shapes Vonnegut’s graphs can take on. To be more precise, when running a random sample, there are six 90% of the time, whereas 10% of the time, the computer will find seven. If you’re interested, Jockers has made available his analysis tools on Github, wherein you can run any story through to determine which of the fundamental plot archetypes it falls under (https://github.com/mjockers/syuzhet). I won’t get into Jockers’ work here, but if you’d like to find out more, you can read about his research on his website. Or, if you’d prefer a scholarly article with less scientific jargon, read about what makes the profile of a bestseller here.

That completes my tour of plot archetypes. I hope you learned something, and more importantly, that this survey has inspired you to do further research into plot and what plot is, so you can add this to your storytelling and, as Aristotle insisted, stir the emotions of your audience.

Stay tuned for more on the journeys and storytelling structures and how we can explore the wild, wild west of storytelling in the epic fantasy genre!

Such a great post, John! I especially love your cavalcade of examples—very helpful for putting these concepts into a relatable state for those of us (me) who might’ve had trouble with them in the past.

Thanks, Elan! I’m so glad you found this helpful. Doing the research to put this all together taught me a lot as well. Which archetype draws you the most?

There are elements of more than one that appeal to me. This notion of archetypical structure is being explored by the folks at Writing Excuses this year. Very interesting indeed. You might enjoy their podcast. 🙂

You’ve just convinced me to start listening! I have started listening to YouTube writing lectures and podcasts whenever I have long car rides (usually when I’m driving to the gym for my weight workouts). Thanks for pointing me toward another adventure!